Summary of Article Published in Volume 14, Special Issue 2 (Colonial Institutions and African Development) in April 2018 by Dácil Juif, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, and Ewout Frankema, Wageningen University. The full article is available here.

The Central African Copperbelt offers a fascinating case for a comparative study of colonial institutional development. We conducted an in-depth study to understand how the colonial administrations and mining companies confronted the problem of labour scarcity. We show that colonial institutions were far from static and difficult to pin down as either extractive or inclusive. Especially in the Belgian Congo an impressive shift occurred from outright coercion to progressive compensation within just a few decades time. This study calls for dynamic conceptualizations of colonial institutions to counterweight their oft-supposed persistence in the historical economics literature.

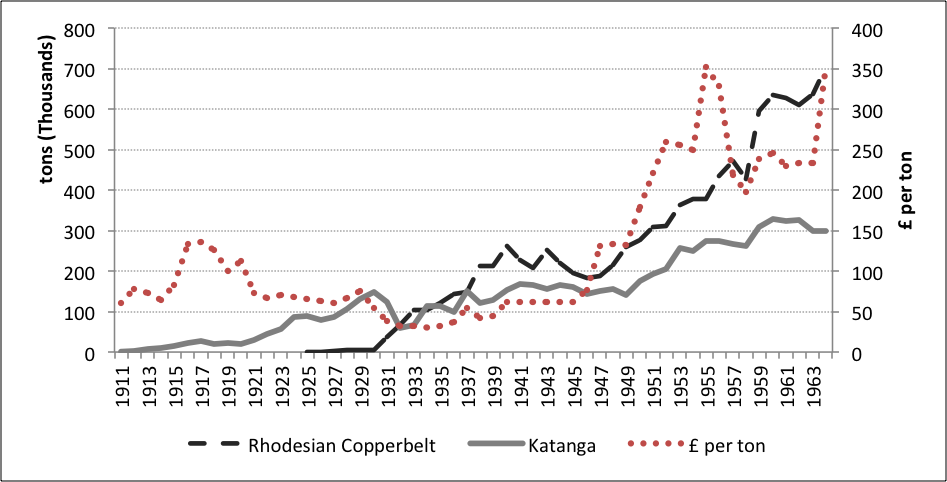

After the discovery of copper deposits in the first decade of the twentieth century, European investors and mining companies were confronted with the problem of labour recruitment in a very low-populated area deep within the interior of the African continent. Local African populations had very few incentives to leave their families for harsh and extremely dangerous work in the mines, especially with fresh memories of the atrocities committed during King Leopold’s rubber campaigns in recent years (c. 1890-1905). Moreover, right through the mining area ran a colonial border separating the Katanga province of the Belgian Congo from the Copperbelt province of British-ruled Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia). This border became important in the late 1920s, when companies on the Rhodesian side began to compete with their counterparts on the Katangese side for already scarce labour supplies. Colonial agents and European prospectors were attracted to the huge possibilities for economic profit. Except for a temporary fall in copper prices in the early 1930s, copper prices and profits of this industry increased steadily until the mid-1970s (see Figure 1). But how did the mining companies solve the problem of labour shortage?

Source: See Juif and Frankema (2018)

From coercion to compensation

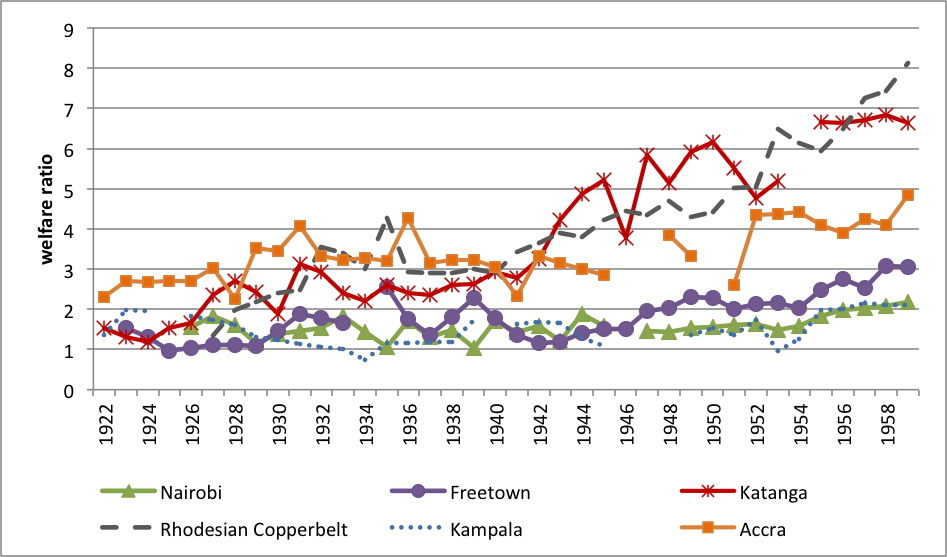

Solutions to the labour problem could be pursued in two directions: coercion or compensation. From 1910 onwards, both directions were tried, but the general trend was a fundamental transition from outright coercion, often at gunpoint and with ample use of physical violence, towards so-called labour stabilization policies, which offered one of the most extensive welfare systems ever created under colonial rule in sub-Saharan Africa. In this article, we reconstruct real wages of mining workers on both sides of the Congolese-Rhodesian border between the 1910s and the 1960s – using the ‘barebones subsistence basket’ deflation method (Allen 2001) – to offer an impression of the implications of this shift. Our calculations, reflected in Figure 2, show that copper mine workers lived at barebones subsistence in the 1910s-1920s, but experienced rapid welfare gains from the mid-1920s onwards and became among the best-paid manual labourers in sub-Saharan Africa from the 1940s. Compensation levels for African workers in Katanga and the Rhodesian copper mines were also notably higher compared to the gold mines of South Africa.

Sources:For Katanga and Rhodesian Copperbelt: Juif and Frankema (2018); for other African cities: Frankema and van Waijenburg (2012)

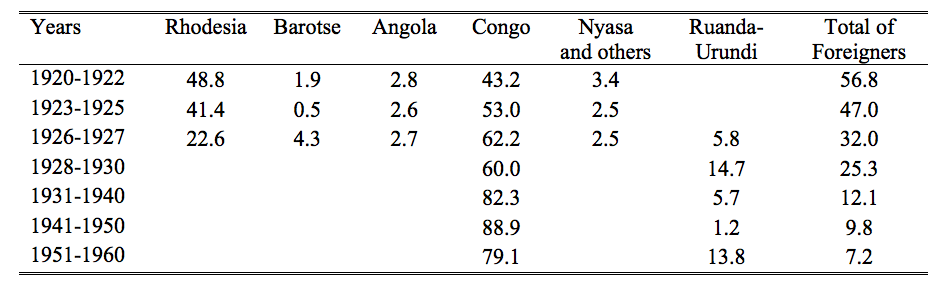

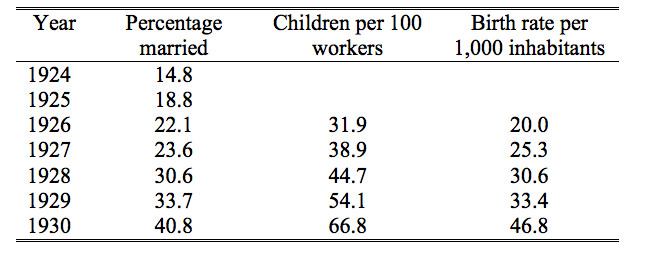

The compensation levels of African copper mine workers rose impressively as coercive labour recruitment practices were replaced by voluntary migration and stabilized workforces. However, confronted with endemic shortages of mining labour, the Congolese mining company UMHK continued to use both ‘carrot’ and ‘stick’, recruiting labour from distant regions up to 1960, with the support of the colonial government. In the first two decades of its existence, the UMHK recruited most African workers in Northern Rhodesia, Angola, Nyasaland and other colonies, but when prospectors started to explore the possibilities for copper mining in Norther Rhodesia in the mid-1920s, the British administration was less inclined to cooperate. The UMHK had to rely increasingly on – voluntary – labour from Belgian dependencies, including more densely populated Ruanda-Urundi (Table 1). The Rhodesian mines concentrated more heavily on circular migrant workers, most of whom came from areas under British or Portuguese control.

Source: Annual Reports UMHK – Main-d’oeuvre indigène

Note: From 1928 on, the place of origin of non-Congolese or Rwandan was not specified anymore, but they were all categorized as ‘foreigners’.

Cross-border differences in labour policies

Despite the similarities in real wage trends, there were distinctive differences in labour policies between the Congo and Rhodesia, which can be explained by the different constraints that companies were facing on both sides of the border. Rhodesian copper companies paid significantly higher shares of remuneration in cash relative to food and housing rations (cash wage c. 65-85% of total compensation between 1930-1960), compared with Congolese companies, which provided 35-50% of remuneration in cash wages.

Rhodesian companies relied primarily on circular migrant workers who would go back to their villages after completing their contracts and preferred to take cash with them. The Rhodesian colonial government supported this practice, as it generated a source for tax revenues in rural hinterlands and, more importantly, prevented the emergence of a ‘de-tribalized’ working class. The British colonial government feared that people who would become permanently detached from their home communities, were a potential threat to the stability of the colonial order.The Congolese government, instead, embraced the labour stabilization programs of the mining industry wholeheartedly. The challenges of recruiting workers were much larger than in Northern Rhodesia, where demand was met with voluntary supply. Failure to attract workers, threatened the growing revenue flow into state coffers, especially after Rhodesia prohibited Congolese companies from recruiting workers in their territories from the mid-1920s onwards. Companies in Katanga started to invest heavily in the quality of additional welfare facilities such as medical care, schooling and housing, all with the objective to tie workers and their families to the mines. From the 1920s onwards, the state-owned UMHK preferred to attract married workers and actively promoted the birth of children. Families of mine workers were thus providing and caring for a new generation of able-bodied mine workers that were to settle permanently in the region (see Table 2).

Source: 1930 Report of the Health Inspector of Northern Rhodesia on Native Labour in Katanga

In order to replace more expensive European workers in various managerial and technical positions, investments were made in African children’s education and workers’ skills. Catholic missions took care of a large part of these services (i.e. education, medical care) and constituted, together with the companies and the provincial and central government, a system of ‘paternalist’ rule, which was quite distinct from the system that developed in Northern Rhodesia. While company owners were increasingly in favour of stabilization policies, the Rhodesian government remained opposed to the expansion of mining towns and cities with potentially high rates of unemployed and destitute people. Moreover, an influential minority of white mining employees, organised in white trade unions, prevented the advancement of Africans into higher ranks and defended a strict maintenance of the ‘colour bar’. Ironically, those trade unions also set an example for the creation of the Northern Rhodesian African Mine Workers’ Union, which managed to negotiate some substantial improvements in working conditions in the late colonial era (Berger 1974). However, neither white nor black trade unions were permitted in the Belgian Congo until after WWII (Katzenellenbogen 1975).

Lessons about institutional development

The labour shortage problem in the Central African Copperbelt reveals how responsive colonial institutions were to changing historical conditions, and how difficult it is to capture the nature of colonial institutions in time-invariant variables. As solutions to the problem of labour scarcity in the Central African Copperbelt varied across space andtime, there is a clear need for dynamic conceptualizations of colonial institutions.

As the production of copper scaled-up, the Katangese mining companies discovered that forced labour recruitment practices were never going to meet their needs, especially in the context of increasing competition for migrant labour. Moreover, international pressure to improve the plight of African labour, made it increasingly costly to pursue with practices of outright coercion. During the 1920s, mounting criticism on the violent treatment of African labour recruits from colonial officials as well as international organizations (i.e. the ILO) raised the need for policy reforms, in the same way as earlier international outrage had put an end to the horrible rubber campaigns. Meanwhile, the growth of the Rhodesian mining industry after the depression of the 1930s was aided by a continuous influx of voluntary labour migrants, making active recruitment redundant.

Yet, neither of these industrial systems could cope with the dramatic collapse of the copper mining sector shortly after independence. World market prices of copper plummeted during the 1970s and did not revive again until the mid-1990s. Once the hallmark of capitalist growth in Africa, the demise of the Copperbelt dragged down the economies of Zambia and Zaire, and both countries remain among the poorest in Africa. Workers who once settled in booming mining towns had to look again for different ways to make a living, and the welfare systems of redundant stabilization policies rapidly fell apart.

References

Allen, R.C. (2001), ‘The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War’, Explorations in Economic History, 38(4): 411- 447.

Berger, E. (1974), Labour, Race, and Colonial Rule, the Copperbelt from 1924 to Independence, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankema, E. and M. Van Waijenburg (2012), ‘Structural Impediments to African Growth? New Evidence from Real Wages in British Africa, 1880–1965’, The Journal of Economic History72(4): 895-926.

Juif, D., & Frankema, E. (2018). From coercion to compensation: institutional responses to labour scarcity in the Central African Copperbelt. Journal of Institutional Economics, 14(2), 313-343.

Katzenellenbogen, S. E. (1975), ‘The Miner’s Frontier, Transport and General Economic Development’, in P. Duignan and L. H. Gann (eds.), Colonialism in Africa (1870-1960), Vol. 4: The Economics of Colonialism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 360–426.

Northern Rhodesian Chamber of Mines Year Books (1956–1963), Kitwe: Mardon Printers.