Summary of JOIE article (First View 6 July 2021) by Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Centre Emile Bernheim and Dulbéa, Université libre de Bruxelles, and Khalid Sekkat, Centre Emile Bernheim, Université libre de Bruxelles. The full article is available on the JOIE website.

Empirical studies of the impact of democracy on growth long remained inconclusive as the meta-study by Doucouliagos and Ulubaşoğlu (2008) shows. However, when the focus shifted from the impact of democracy to the impact of the transition to democracy, the results became consistently more optimistic. Considering various methods, samples, and time horizons, Hausmann et al. (2005), Rodrik and Wacziarg (2005), Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008), Madsen et al. (2015), and Acemoglu et al. (2019) observed that countries that democratize do grow faster than before. In their paper, Méon and Sekkat (2021) investigate a channel of transmission from democracy to growth by tracking the evolution of institutional outcomes around democratic transitions.

Institutional outcomes, such as the rule of law, corruption or political instability, have been repeatedly found to be critical to growth and development (Knack and Keefer, 1995, Acemoglu et al., 2001). However, while de jure democracy may be established virtually overnight, de facto institutional outcomes take time to adjust, if they ever do. Democratization will not necessarily trickle down to the behavior of agents affecting the rule of law, corruption or political instability.

The timing of the effect of democratic transitions matters at least as much as its nature. Firstly, the faster institutional outcomes improve, the faster growth will increase. Secondly, the speed at which institutional and economic outcomes adjust after a democratic transition affects the stability of emerging democracies. If those outcomes adjust too slowly, disappointment might lead to unrest and even to autocratic reversals (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2001).

To address the issue, Méon and Sekkat (2021) apply a method that was applied to growth by Rodrik and Wacziarg (2005), Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008b), and Acemoglu et al. (2019). Specifically, they study the change over time in the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) index, and in its components, around episodes of democratic transitions using a panel of 135 countries during the “third wave” of democratization, specifically 1984-2012.

Because the method focuses on the within dimension of the relationship, it allows tracking the evolution of countries’ institutional outcomes around their democratic transitions, which is more precise than comparing different countries with different levels of democracy (Papaioannou and Siourounis, 2008). The method moreover sidesteps the debate on the correct measurement of democracy because it only needs to identify democratic transitions but not to measure their degree.

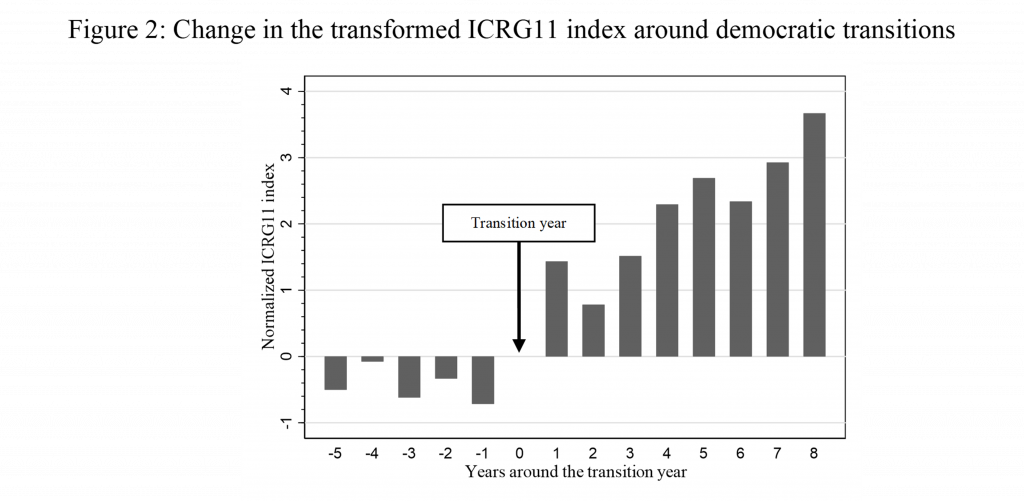

Figure 1 below summarizes the main finding of Méon and Sekkat (2021). It plots the average evolution before and after transitions of the International Country Risk Guide Index. The component of the index measuring the level of democracy was removed, to avoid estimating a tautological relationship.

The Figure shows that the index follows no particular trend before transitions. This is noteworthy, because it suggests that countries where a transition occurs are not different from other countries during the five years leading to the transition. It therefore lends credence to a causal interpretation of the results of Méon and Sekkat (2021). After the transition, the index improves and trends upwards. As a result, five years after the transition, the index is on average 4.48 points higher than in the transition year and 5.19 points higher than in the year immediately preceding the transition. Such an improvement would not bring a developing country to Western European standards, but it is non-negligible. It amounts to a third of the standard deviation of the index in our sample. It is of the same magnitude as the differences between the indices of Iran and India, between the indices of Nigeria and Ivory Coast, or between the indices of Mexico and Costa Rica, at the end of the period that Méon and Sekkat (2.21) study.

Méon and Sekkat (2021) complement Figure 1 by a series of estimations of their econometric model. Their estimates suggest that democratic transitions improve institutional outcomes, and that the bulk of the improvement occurs during the three years following the transition. Again, they find no anticipation effect. The result is robust to alternative definitions of transitions, to alternative codings of pre- and post-transition years, to changing the set of control variables, to excluding former socialist countries, and to addressing endogeneity. Both full and partial democratic transitions improve institutional outcomes. In contrast to other democratic transitions, transitions out of military regimes and transitions out of communist autocracies do not improve institutional outcomes. Finally, the effect is particularly clear on the corruption, law and order, and military in politics dimensions of the index.

Those results have several implications for recent and future democratic transitions. They firstly suggest that while to everything there is a season, the institutional benefits of democratic transitions can on average be reaped within a time horizon of three years. At the same time, the benefits, though significant, will not cure democratizing countries of their institutional deficiencies. A conservative estimate of the impact of transitions on political risk amounts to a third of the standard deviation of the index of institutional outcomes.

One must note that the pattern reported by Méon and Sekkat (2021) is an average. Admittedly, they show that the effect of transitions is conditional on GDP per capita and education but these findings do not make in-depth country analyses pointless.

Finally, while the results uncover one channel through which democratic transitions may increase growth, it is not the only one. Furthermore, the impact of democratic transitions on institutional outcomes can only be the first in a series that will result in growth-friendly policies leading to better economic outcomes. Uncovering those links is food for future research.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson, 2001. “A theory of political transitions.” American Economic Review, 91 (4): 938–963.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson, 2008. “Persistence of power, elites, and institutions.” American Economic Review, 98 (1): 267–293.

Acemoglu, Daron, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson, 2019. “Democracy does cause growth.” Journal of Political Economy, 127 (1), 47–100

Doucouliagos, Hristos and Mehmet A. Ulubaşoğlu, 2008. “Democracy and economic growth: A meta-analysis.” American Journal of Political Science, 52 (1): 61–83.

Hausmann Ricardo, Pritchett, Lant, and Dani Rodrik, 2005. “Growth accelerations.” Journal of Economic Growth, 10 (4): 303–329.

Knack Steve and Philip Keefer, 1995. “Institutions and economic performance: cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures.” Economics and Politics, 7, 207–227.

Madsen, Jakob B., Paul A. Raschky, and Ahmed Skali, 2015. “Does democracy drive income in the world, 1500–2000?” European Economic Review, 78, 175–195.

Papaioannou, Elias, and Gregorios Siourounis, 2008. “Democratisation and growth.” Economic Journal, 118, 1520–1551.

Rodrik, Dani, and Romain Wacziarg, 2005, “Do democratic transitions produce bad economic outcomes?” American Economic Review, 95 (2): 50–55.