Summary of JOIE article “Institutions and Place: Rethinking the Political Economy of the Resource Curse”, by José Carlos Orihuela (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú). The article is available on the JOIE website.

The resource curse debate has become a somewhat deadlocked academic conversation. Curse or blessing? Well, it depends. I argue that the way in which resource curse mechanisms unfold are likely to vary with contextual specificities, and so theory and history need to talk to each other. It makes perfect sense to observe that resource wealth reaps success in some cases and failure in others; or that a case of a blessing (curse) becomes a curse (blessing) over time.

If one understands economic development in terms of an evolutionary framework based on multiple equilibria, the single equilibrium is considered a feasible but unlikely possibility. Yet too many social scientists — economists above all — have been searching for a universal law or theorized single equilibrium with regard to resource-based development. Therefore, an otherwise fruitful exchange of simplifying theories, statistical trends, and detailed qualitative research too often becomes a static quarrel among one-truth holders.

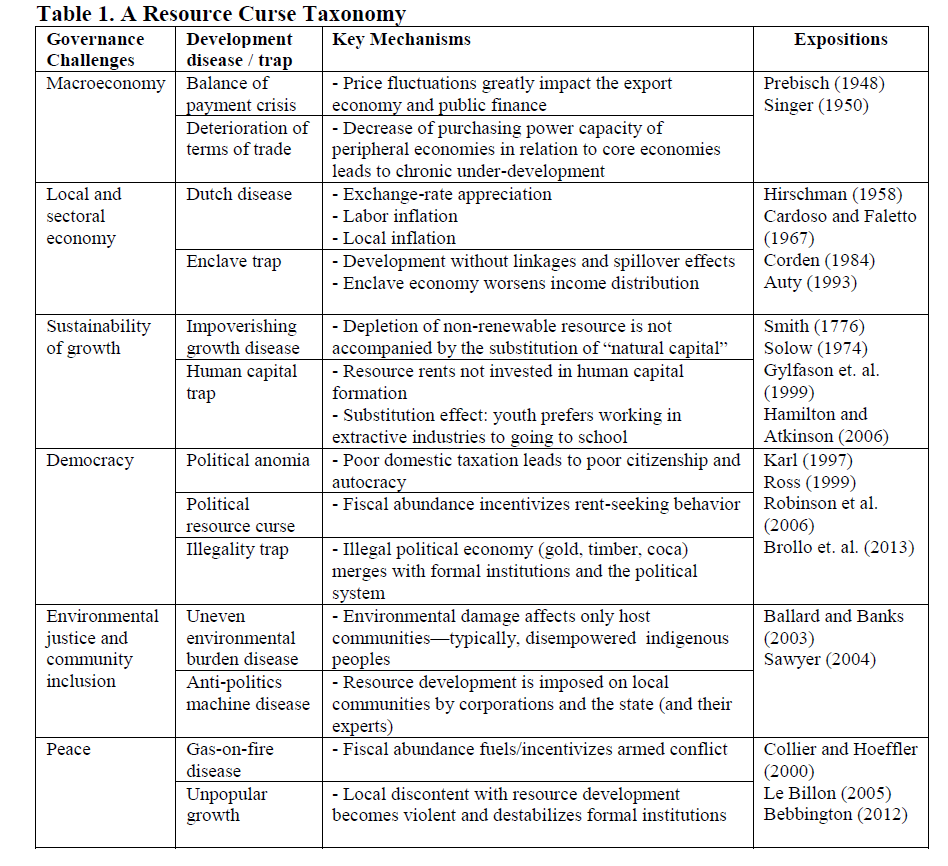

If revised properly, the array of seemingly conflicting findings of resource-curse literature presents many lessons. What do we know? That there is a curse and there is a blessing, and there is no single typical case. Why and how? There are a number of stylized mechanisms that could, in principle, be contributing to a curse, Table 1 tells:

The taxonomy illustrates the variety of associated, but essentially different, social phenomena classified as the resource curse. When referring to the resource curse, conventional economists will commonly discuss national economic growth figures, which under this framework classifies as the macroeconomic variety of the resource curse. Many more governance dimensions of economic well-being come into play, each entailing one or more curse forms: the Dutch Disease, the enclave curse, the unsustainability of economic growth curse, the political resource curse, the environmental justice curse, the conflict curse, and so on. Thus, governance challenges go beyond short-term GDP growth rates or equivalent short-term local economy income.

However, having a taxonomy of resource curse diseases does not mean that every single case of resource abundance is to fall into all of the identified development traps/diseases. Besides the fact that “natural capital” is not the only relevant factor contributing to development, historical contingency matters and it would be fallacious to assume that all units of analysis are subject to the same historical—temporal and spatial—context. Resource-based development does not take place in a void.

I find that there is a need to “bring the structure back in” to the analysis of economic development. In all six governance challenges defined in Table 1, institutions and place matter to some extent. However, because of the influence of narrow views within neoclassical economics, which has permeated the field of political science, most resource-curse literature either oversimplifies or ignores the significance of institutions, place and any other structure contextualizing human behavior.

All too commonly, in particular, mainstream economic literature defines institutions and their roles in the narrowest terms. Flaws stem from assumptions on human behavior (ultra-selfish rationality) and what constitutes good institutions (property rights and the minimal yet efficient state), the quality of the data used, and the assumptions of how institutions evolve over time and (do not) vary across space.

There is need not only to rethink the resource curse, but also to revise the conventional institutions-matter line of argumentation. Two overarching ideas should guide a “context matters” political economy of the curse: (i) resource-based development is geographically uneven; and (ii) spatially heterogeneous institutions are likely to condition the relationship between natural resources and development outcomes. The call being to embrace complexity, the proposed perspective also identifies development as multidimensional, with six governance challenges to recall in this regard: the macroeconomy, the local and sectoral economy, the sustainability of economic growth, democracy, environmental justice and community inclusion, and peace. Thus, I am advocating research programs that improve our understanding of how institutions and place relate to these challenges of resource-based development.

Context-matters political economy perspectives can greatly contribute to filling the gap with “more nuanced, layered explanations” of the resource curse. Resource-related or not, rationality – and therefore agency – is bounded, embedded in society and shaped by temporal and spatial contingency. Qualitative research illuminates such complexity and provides the micro-foundations critical for social science analysis.

José Carlos Orihuela (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú)